Anzia Yezierska’s New York

Anzia Yezierska’s Bread Givers

Book I: Hester Street

“On the corner of the most crowded part of Hester Street I stood myself with my pail of herring. “Herring! Herring! A bargain in the world! Pick them out yourself. Two cents apiece.” My voice was like dynamite.Louder than all the pushcart peddlers,” louder than all the hollering noises of bargaining and selling. I cried out my herring with all the burning fire of my ten old years.” So loud was my yelling, for my little size, that people stopped to look at me. And more came to see what the others were looking at.”(21).

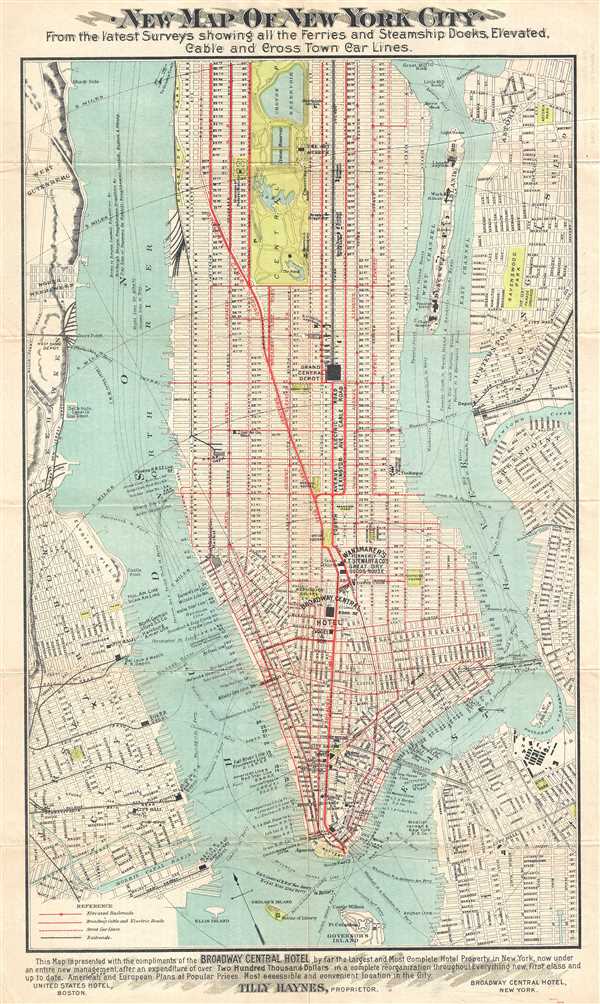

“Mammeh!” I begged. “Let me only go out to peddle with something. I got to bring in money if no one is working. “Woe is me!” Mother cried. “How can I stand it? An empty head on one side and craziness on the other side” Nobody is working and we got to eat,” “I kept begging. “If I could only peddle with something I could bring in money. “Let me alone. Crazy head. No wonder your father named you.”Blut-und-Eisen,“When she begins to want a thing, there is no rest, no let-up until she gets it.”(20) Here is a Map that shows what Manhattan looked like in the 1900.

Historical Map on New York City 1900

“Louder than all the Pushcart Peddlers, louder than all the hollering noises of bargaining and selling, I cried out my herring with all the burning fire of my ten old years. So loud was my yelling, for my little size, that people stopped to look at me. And more came to see what the others were looking at.” “Give only a look on the saleslady, “laughed a big fat woman with a full basket. “Also a person,” laughed another also fighting already for the bite in the mouth.” “How old are you, little skinny bones? Ain’t your father working?”(21)

“I’m going to hear the free music in the Park tonight,”She laughed to herself, with the pleasure before her,”and these pink roses on my hat to match out my pink calico will make me look just like the picture on the magazine cover” Bessie rushed over to Mashah’s fancy pink hat as if tear it to pieces, but instead, she tore her own old hat from her head, flung it on the floor, and kicked it under the stove”(3)

“ When Mashah walked in the street in her everyday work dress that was cut from the same goods and bought from the same pushcart like the rest of us it looked different on her. Her clothes were always so new and fresh, without the least little wrinkle”. Like the dressed – up doll lady from the show window of the grandest department store. Like from a born queen it shines from her. The pride in her beautiful face, in her golden hair, lifted her head like a diamond crown Mashah worked when she had work; but the minute she got home , she was always busy with her beauty” (4).What was “Fashionable on Hester Street.? In the early 1900

“Suddenly, it grew dark before our eyes.The collector lady from the landlord! We did not hear her till she banged open the door. Her hard eyes glared at Father “My rent !” she cried,waving her thick diamond fingers before Father’s face. But he didn’t see her or hear her. He went on chanting” “Awake! Awake! Put on strength, O arm of the Lord: Awake, as in ancient days, in the generations of old. Art thou not he that hath cut Rahab and wounded the dragon?” “Schnorrer!” shrieked the landlady , her fat face red with a far-off look, “what do you want?” “Don’t you know me ? Haven’t I come often enough? My rent! My rent ! My rent I want!”(17).

Book II: Between Two Worlds

“Blindly, I grabbed my things together into a bundle. I didn’t care where I was going or what would become of me. Only to break away from my black life. Only not to hear Fathers preaching voice again. As I put on my hat and coat, I saw Mother, clutching at her heart in helplessness, her sorrowful eyes gazing at me. All the suffering of her years was in the dumb look she turned on me. Bending over, she took out from her stocking the red handkerchief with the knot that help her saved-up rent money. And without a word, she pushed it into my hand. As I came through the door with my bundle, Father caught sight of me. ‘What’s this?’ he asked. ‘Where are you going?’ ‘I’m going back to work, in New York.’ ‘What? Wild-head! Without asking, without consulting your father, you get yourself ready to go? Do you yet know that I want you to work in New York? Let’s first count out your carfare to home every night. Maybe it will cost so much there wouldn’t be anything left from your wages.’ ‘But I’m not coming home!’ ‘What? A daughter of mine, only seventeen years old, not home at night?’ ‘I’ll go to Bessie or Mashah.’ ‘Mashah is starving poor, and you know how crowded it is by Bessie.’ ‘If there’s no place for me by my sisters, I’ll find a place by strangers.’ ‘A young girl , along, among strangers? Do you know what’s going on in the world? No girl can live without a father or a husband to look out for her. It says in the Torah, only though a man has a woman an existence. Only through a man can a woman enter Heaven.”(136-137)

“Turning me out in the street like dirt…Only to make myself somebody great-and have them come begging favours at my feet…A girl-slaving away in the shop. Her hair was already turning gray, and nothing had ever happened to her. Then suddenly she began to study in night school, then college. And worked and studied, on and on, till she became a teacher in the school. A school teacher-I! Saw myself sitting back like a lady at my desk, the children, their eyes on me, watching and waiting for me to call out the different ones to the board, to spell a word, or answer me a question. It was like looking up to the top of the highest skyscraper while down in the gutter. All night long I walked the streets, drunk with my dreams” (155).

“How strong, how full of life and hope I felt as I walked out the bakery. I opened my arms, burning to hug the new day. The strength of a million people was surging up in me. I felt I could turn the earth upside down down with my littlest finger. I wanted to dance, to fly in the air and kiss the sun and stars with my singing heart. I, alone, with myself, was enjoying myself for the first time as with grandest company” (157).

“I want a room all alone to myself.” “I was ready to drop from weariness when I saw a crooked sign, in a scrawling han, “Private room, A Bargain Cheap.” It was a dark hole on the ground floor, opening into a narrow shaft. The only window where some light might have come in was thick with black dust. The bed see-sawed on its broken feet, one shorter than the others. The mattress was full of lumps, and the sheets were shreds and patches. But the room had a separate entrance hall. A door I could shut. And it was only six dollars a month… I looked at the room. A separate door to myself- a door to shut out all the noises of the world, and only six dollars. Where could I get such a bargain in the whole East Side?” (158-159)

“What do you want to learn?” asked the teacher at the desk. “I want to learn everything everything in the school.” She raised the lids of her cold eyes and stared at me. “Perhaps you had better take one better take one thing at a time, she said indifferently. “There’s a commercial curse, manual training-” “I want a quick education for a teacher” I cried. A hard laugh was my answer. Then she showed me the lists of the different classes, and I came out of my high dreams by registering for English and arithmetic. Then I began five nights a week in a crowded class of fifty, with a teacher so busy with her class that she had no time to notice me” (162).

“Ten hours I must work the laundry. Two hours in the night school. Two hours more to study my lessons. When can I take time to be clean? If I’m to have strength and courage to go on with what I set out to do, I must shut my eyes to the dirt” (163)

“Don’t you know they always give men more?” called a voice from the line. It takes a woman to be mean to a woman,” piped up another. “You’re holding up the line,” said the head lady, coming over, with quiet politeness…People began to titter and stare at me. Even the girl at the serving table laughed as she put on a man’s plate a big slice of fried liver, twice as big as she would have given me. “Cheaters! Robbers!” I longed to cry out to them. Why do you have flowers on the table and cheat a starving girl from her bite of food? But I was too trampled to speak. With tight lips, I walked out” (169).

“He wants me to be dressed in the latest style, yet he kicks I’m spending all his money. He wants everything grand but cheap. When I pay a hundred dollars for a suir, I’ve got to tell him it’s fifty. To keep his mouth shut and to not have any fights. I feed him with lies. Getting money from him is like pulling teeth. These diamonds that you see on me, that’s his saving bank. He buys me jewellery, only to show me off to his friends that’s he’s so rich” (175).

“I studied myself in the mirror. I examined, one by one, the features that gazed back at me. Tired eyes. Eyes that gazed far away at nothing. A set sadness about the lips like in old maid who’d given up all hopes of happiness. A gray face. A stone face. Turned to stone from not living. A black shirt waist, high up to the neck. Not a breath of colour. Everything about me was gray, drab, dead. I was only twenty-three and I dressed myself like an old lady in mourning” (181).

“Think, only, I never yet went inside a school or a college in America,” he went on. “And I have American-born college men working for me as book-keepers and salesman. I can hire them and fire them, as it wills itself in me. Because with all their college education they haven’t got the heads to make the money that I have” (191).

“Any one listening to you would think that lodge meetings and money-making are the beginning and the end of life. .. Money-making is the biggest game in America” (196).

“He had given up worldly success to success to drink the wisdom of the Torah. He would tell me that, after all, I was the only daughter of his faith. I had lived the old, old story which he drilled into our childhood ears-the story of Jacob and Esau” (202).

“It says in the Torah: What’s a woman without a man? Less than nothing-a blotted out existence. No life on earth and no hope of heaven” (205)

“That burning day when I got ready to leave New York and start out of my journey to college! I felt like Columbus starting out for the other end of the earth. I felt like a pilgrim fathers who had left their homeland and all their kin behind them and trailed out in search of the New World” (209).

“Like a dream was the whole night’s journey. And like a dream mounting on a dream was this college town, this New America of culture education. Before this, New York was all of America to me. But now I came to a town of quiet streets, shaded with greens. No crowds, no tenements. No hurrying noise to beat the race of the hours. Only a leisured quietness whispered in the air. Peace. Be still. Eternal time is all before you” (210).

Book III: The New World

“Home! Back to New York! Sara Smolinsky, from Hester Street, changed into a person! Kid gloves were on my hands. All my things were neatly packed in a brand-new leather satchel. Who would believe, as I took m seat with the quiet stillness of a college lady, how I was burning up with excited pride in myself. I was like a person who had climbed to the top of a high mountain and was still breathless with his climb. If only I could have taken out my diploma and held it over my head for all to see! I was a college graduate! I was about to become a teacher of the schools!” (237).

My God! She’s dying. Mother is dying! I tried to think, to make myself realize that Mother, with all this dumb sorrow gazing at me, was passing, passing away, for ever. But above the dull pain the pressed on my heart, thinking was impossible. I felt I was in the clutch of some unreal dream from which I was trying to waken. Tiny fragments of memory rushed through my mind. I remembered with what wild abandon mother had danced the kozatzkeh at the neighbour’s wedding. With what passion she had bargained at the pushcart over a penny… How her eyes sparked with friendliness as she served the glasses of tea, spread everything we had on the table, to show her hospitality. A new pair of stockings, a clean apron, a mere car ride, was an event in her life that filled her with sunshine for the whole day” (251).

“The windows of my classroom faced the same crowded street where seventeen years ago I started out my career selling herring. The same tenements with fire escapes full of pillows and feather beds. The same weazened, tawny-faced organ-grinder mechanically turning out songs that were all the music I knew of in my childhood. How intoxicating were those old tunes of the hurdy-gurdy! I’d leave my basket of herring in the middle of the sidewalk, forget all my cares, and leap into the dance with that wild abandon of children of the poor” (269).

“One of Mr. Seelig’s special hobbies was English pronunciation, and since I was new to the work, he would come in sometimes to see how I was getting on. My children used to murder the language as I did when I was a child of Hester Street. And I wanted to give them that better speech that the teachers in college had tried to knock into me. Sometimes my task seemed almost hopeless. There was Aby Zuker, the brightest eleven-year-old bot in my class of fifty. He had the neighbourhood habit of ending almost every sentence with ‘ain’t it.’” (270-271).

We have print # 250 of the original print of this map.